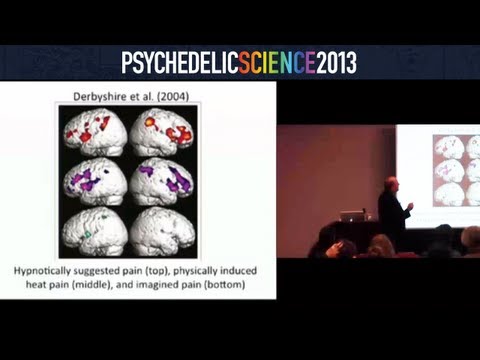

[The Neural Correlates of Altered Consciousnes :02[From Hypnosis and Meditation to Drug-Based Changes] [Amir Raz, M.D. April 21, 2013] We have about 25 minutes to talk about altered consciousness from my perspective, or a little bit of my perspective. So let me tell you just a little bit in [the] way of context. First of all, I'm very happy to be here in a conference that has the title "psychedelic science," for all kinds of reasons that you'll see in a few minutes. My first slide basically says that I'm a professional scientist. Professional science is a weird profession. You get paid basically to do something you would probably do for free, not paid a lot, but paid to do something that you really love, you're really passionate about, and I happen to be very passionate about consciousness. One thing that I do in order to study consciousness is to look at altered consciousness. When I was a graduate student, it was almost unheard of that a graduate student, at least, would say that they want to study consciousness. This was not centuries ago. [It] was pretty recently. The scientific community in general is pretty conservative and pretty skeptical of weird stuff. Altered consciousness is considered weird stuff today. It's slightly changing; I want to show you a little bit how it's changing and the kind of stuff that we need to do in order to make it change. Before that I want to show you that the approach that we take to altered consciousness is an interdisciplinary one. My background is in computational signs and psychology and computer science, things like that. For the past 15 years or 20 years or so, I've been in psychiatry departments and psychology departments and neurology departments. McGill, for those of you who are not familiar with Canada, it's a foreign but friendly country, just north of the United States. McGill University is sort of the Harvard of Canada, or as they say in Canada, Harvard is the McGill of the south. We have labs at McGill, and some of my studies, not all of them, but some of them are dedicated to altered consciousness and I want to show you just a few things. I'd like to start with some kind of a context. So you see, in life, it's very easy, especially when you give a 25-minute presentation, it's very easy to classify people in a caricatured way into one or two, one or the other. So, "do you take psychedelic drugs or" "do you not? Do you believe in psychedelic drugs or do you not?" "Are you spiritual or are you not? Are you rich or poor, a giver," "a taker?" and so on. A lot of times in science, you hear things like "you're not open-minded enough," "you're not open-minded," or "you're close-minded." The fact of the matter is that this kind of dichotomy, "are you on this side or are you on that side" becomes all the more acute when you talk about things where quantitative science has very little to offer or not enough to offer. And then, qualitative science, which is a form of science, a legitimate form of science, is considered by some people to be very soft. By some people it's not even considered to be science at all. As a matter of fact, this is true for social science in general. So people who are doing social science, sometimes when they come into interaction[s] with clinicians or with medical types, sometimes are being discounted or dismissed or disparaged just based on their academic grooming, which is a very strange thing to happen in an educated society, but still it happens. Now, let's start with a very basic question. I think that this question actually captures the crux of what I'm about to say here today. Let's say that you wanted to study altered consciousness, or you wanted to experience it, and I gave you a two-choice, forced-choice question. So, would you take 40 years and go into a cave and study meditation to achieve this altered experience, or would you ingest something and have it in a few seconds? Very difficult question. It's a very difficult question, but this question, actually, is very pertinent to what we're talking about, and specifically it's pertinent for young people. I'll explain why in a little bit, but in western culture, there's no question in our culture, that we're migrating towards B. There's no question about that. Yes, there's some cultures, and there's a long tradition, not a negligible one of A, and there [are] other options; I'm just making a caricature out of it to make a point. But I think that this question is essential, because western culture is very impatient. We want to lose weight for the wedding tomorrow. We want to look good. We want things to happen very quickly, and this is a way to make things work very quickly. Then there's a whole cultural and social and legal [aspect] of it in the background that we can work out. I want to tell you a word or two about science, because I am a professional scientist and I work among scientists. Scientists have a very formal way of thinking about what they do. In the slide of the nudist beach, they separate the world into into scientists and non-scientists, unfortunately. Usually, when you're talking about science, you are in a situation where people ask questions, because people like to ask questions. Some of the questions are unscientific. What can you do? "Who should I marry?" is not a very scientific question. "Do you believe that hypnosis can reduce pain," Is not a very scientific question. "How should I invest my money?" believe it or not, is not a scientific question. "Do you suppose" "that suggestion can help depression?" is also not a scientific question. The answer might be yes, but these are not scientific questions, at least not in the formal sense. That's because a real pristine scientist, a real one, doesn't use words like believe and suppose and things like that. Real scientists go by data. A lot of scientists sometimes are confused, because they confuse the lack of data for data of absence. That's a big problem in general, but it's a big problem with scientists. Often, they'll say "show me the data," but then when you try to do something to collect some data they say, "oh, that's completely unacceptable," or "we can't do that; that's not very scientific." There's a little bit of that, and that's changing with time. Today, especially in neuroscience, in brain science, we have a lot of openness to things that 20 years ago were unheard of, and I'm not talking about technology right now. I'm talking about content fields such as mindfulness, hypnosis, and other things that are very relevant to altered states of consciousness, but are still [a] ways from ingestion of hallucinogenic or psychedelic drugs; we're going to get there in just a second. So, there's some misconceptions that I think people who are dealing or interacting with scientists need to know. These misconceptions are also prevalent among scientists. I think that the first thing that I need to do is educate you a little bit about it. So the first thing is that a lot of people--for reasons that I can expound on, I can wax on this eloquently, but we don't have time--they have this mistaken idea that science is about the truth. Science is not about the truth. I just want you to understand this. Science is not about the truth; we have no monopoly on the truth. Sometimes we endorse things, "this was endorsed by scientists," or whatever. Take it with a grain of salt. The second thing is that science in general does not have any kind of monopoly on quantitative science. Quantitative science is not the only form of science. There are other forms of science including qualitative, and including something that requires subjectivity, unity, spirituality, intentional causation, and so on. So there's nothing unscientific about studying these things, nothing at all that is unscientific based on the scientific paradigm, on the scientific theory. It's very important to understand this because some people dismiss it based on the philosophy of science. They're just not well-read on the philosophy of science. So that's not true either. That's a critical point that should be a point of contention when you're dealing with scientists. Now, I want to explain what science is, in order to show you some of the results that we have about altered consciousness. Science really is a set of institutional structures and techniques, methodologies, that have evolved over time in order to improve our knowledge. Anything that you do to improve knowledge in a systematic way is science. That's why, in this sense, any systematic study, any rigorous investigation of some phenomena, fits the definition of science. That would include many of the things that have to do with consciousness and altered consciousness and so on, although many people feel uncomfortable with that for reasons that have to do more with dogma and history and narrow-mindedness than actual definitions of science. Let's start with some real science. When we are talking about altered consciousness, it's almost impossible...and I've selected a number of studies to show you some kind of a timeline progression into these things, and I decided to also focus on altered consciousness from a perspective that is probably unfamiliar to most of you. That is the perspective of altered consciousness without ingesting anything. I'll show you why that is important, actually. Here's a paper that was published in Science, probably one of the premier journals in the field, and this particular paper is about pain. This paper identifies a particular area in the brain, in the prefrontal cortex, just behind where my finger is. This particular area is called the anterior cingulate cortex, or ACC for short, has been identified by this particular group of researchers. You're not going to believe this, but they're out of Montreal, where McGill is, but they're not at McGill;1 they're at University of Montreal. That's just a fluke. It so happens1 that this particular group of researchers have shown that1 sensations of pain--actually, you can generate pain psychologically,1 and it would be as real; there's absolutely nothing physical to1 cause you pain, but you can actually create a lot of pain in people1 by suggesting it to them, and you can reduce pain by suggesting to them1 all kinds of things that have nothing to do with what's happening1 in reality, and the perception of pain would decrease.1 They actually showed a very nice correlation of the brain activation,1 what's happening inside your head, and what the physical experience is.1 Now, if you know anything about neuroscience, if you know anything about1 brain science, you would very quickly say, "Hey, what's new about that?"1 We know that we live in our brains." We live in our brains. So1 reality as we perceive it is basically what happens inside our brain.1 Yes, that's true, but there's also | an element of hallucination that is1 something that we create in our brain that has nothing to do1 with the world that is actually distinct from things like imagining,1 or things like thinking that something is happening, and so on.1 These are all, at some level... conscious experience[s]...1 these are like ripples in the ribbon of consciousness1 or in the fabric of consciousness. So here's another study [from] 1998.1 I'm sort of taking you in a timeline progression. This is a PET study,1 and this particular study, as well as the previous one, by the way,1 show you that there's a tendency in science, if you want to publish1 in a good scientific journal there's a tendency to have colorful1 brain images, probably better to have them in three dimensions.1 Brain imaging has become the ultimate toy in this game. I'm fortunate1 enough to be a member of the Montreal Neurological Institute,1 in Montreal, where we really have brain toys of the best caliber.1 It's one of the premiere institutions for brain science.1 We just about have every imaginable brain toy that you can think of.1 Any imaging technique that is out there, we have. This is an fMRI study.1 This is a PET study. There's certain advantages to doing PET studies,1 positron emission tomography, when you actually inject people1 with a radioactive tracer, radioactive ligand. ...You'll see in this1 particular study we'll talk about in just a second, again, the same1 area lights up. In this study they did something weirder,1 in the sense that they had people lie in the scanner.1 This scanner is very quiet; fMRI is loud. PET scan is very, very quiet.1 They lie there doing nothing, you get some kind of a baseline1 measurement. You hear instructions, so you have a speaker speaking1 to you, and you get particular activation.1 Then, you imagine that you hear the instructions,1 but actually there are no instructions. So there's quiet, but1 you're asked to imagine the instructions, and here you're hallucinating1 the instructions, but how are you hallucinating this? Somebody induces1 you with a ritual. Somebody induces you into hypnosis, whatever1 that means, and with a hypnotic hallucination, you're basically1 under the impression that you're hearing the sound, or the voice1 that you heard before. But there's actually no voice at all.1 And they showed...again, going back before some of the people1 in this hall were born, that this is actually very similar, these two1 activations at the brain level are very, very similar. Again, shows you1 that when you're imagining something, or when you're hallucinating1 something, it's quite different experiences. Not only that,1 but we're getting the same kind of convergence onto brain areas1 that are well-documented in the literature,1 have something to do with altered consciousness, with awareness,1 and so on. Not only that, but in addition to the brain imaging,1 you can actually do all kinds of qualitative measures, very important,1 that would supplement those brain imaging measures.1 You can actually show a very nice correlation; these are huge1 correlations in scientific terms. The brain activation and what1 the person is experiencing are actually veridical; this is the truth.1 They're not just doing this as a part of role enactment. This is not just1 social compliance. They're not doing it in order to be nice to you.1 They're doing it because this is truly what they're feeling.1 There's a problem when you do, for example, the 1997 study1 that I showed you, there's a problem when you do pain studies,1 because I have no access to your pain. So if you tell me,1 "oh, I'm in a lot of pain. On a scale of 1 to 10 it's 9,"1 I have no way as a scientist to access your pain,1 and...I have no biological marker. That's why a lot of people are1 a little bit disenchanted, or were disenchanted with pain.1 Now pain is sort of swinging back full-stream with the leaders1 in pain research beginning to show that there's sort of semi-objective1 ways to look at pain, so that when you tell me that you have1 a particular pain, I can actually verify that with all kinds of1 biological indices. Science today is extremely...it's almost all about1 objective measurements, and less so about subjective [ones].1 Of course, subjective measurements are very important, but they always...1 in order for subjective measurements to be valid or to be listened to1 carefully, we need to have some kind of an objective measure.1 That's why brain imaging is such a huge revolution in the field of1 consciousness in general and psychology and human behavior.1 Here's another study just 2 years later. This is a Harvard scientist,1 Kosslyn, with a long list of researchers. The last one1 actually from here, from Harvard, David [Spiegelin].1 This is a very simple study. They show people these mondrians,1 either in color or in black and white, and they see them either1 the way they are or sometimes with a suggestion to hallucinate them as1 either in color or in black and white, that goes against the thing.1 So sometimes they'll show this to people and tell them1 "this is actually in black and white." And sometimes they'll show this1 to people and tell them, "this is actually in color."1 These are regular healthy people, who are just highly suggestible,1 highly hypnotizable, whatever that means. They were able to show1 with a bunch of PET scans that the areas that are usually dedicated to1 color vision light up even when you show them black and white figures,1 and the areas that are dedicated to black and white vision1 actually light up when you're actually showing them color vision.1 If I turn it around, you understand what I meant. It's not what I said;1 it's what I meant. So, the same thing happens here with,1 a little bit later, a group of scientists from England showing that1 you can create paralysis, you can convince people that they're paralyzed,1 although they're not paralyzed; there's nothing to paralyze. But1 you can convince them that they're paralyzed, and as a result1 of telling them that they're paralyzed, they actually act like they1 can't move their leg or hand, and you can actually see the area that1 lights up in the brain in response to these suggestions.1 There's absolutely no pharmacological agents present.1 There's absolutely nothing other than words that cross the barrier.1 Again, in the field of pain, people have demonstrated more recently1 that it's possible to show pain in a context of a hallucination.1 You can show a particular form of pain that is induced by heat that1 actually matches this particular description, and you can ask people1 to imagine these things and you can see again, from1 a brain activation standpoint, this is an fMRI study, you can see that1 these two pictures, they look alike. You don't need to be a1 brain scientist. So whether you get "real" pain or whether you are1 "hallucinating" this pain, your brain fries in a similar fashion.1 So that's very interesting, because for people who are in these1 two conditions, the experience is real. It's veridical, despite...1 the fact that there's no physical reality to be congruent with it,1 in this case, only in this case. So it's quite clear that we are1 people who live in our brains. It's quite clear that this is happening,1 it's also clear that studies like these, like these two that I'm1 superimposing one next to the other, are extremely helpful to show this.1 Now, people have taken this pain analogy into slightly more1 emotional domains. They've identified various aspects of pain. Sometimes1 it's emotional pain; sometimes the pain has to do with seeing something1 that is painful in a picture and so on.1 They show that... these are very, very nice correlations between1 specific areas such as the anterior cingulate cortex1 that I mentioned to you. Then there's some rostral areas to it, there's1 some caudal areas to it. So it's the front or the back,1 it doesn't really matter. This is all the geography of the brain,1 or the neuroanatomy of the brain. But the fact of the matter is1 that we are now getting to the point where we understand fully well1 that you can create these changes in a big way.1 A study that I conducted a few years ago...again, I'm just going in1 some kind of a thematic timeline here, showed that I can take1 this area that has to do with altered consciousness, among other things.1 It has to do with cognitive control, it has to do with monitoring, it1 has to do with all kinds of higher cognitive functions that we're1 not going to get into, but definitely, it's involved in the orchestration1 of altered consciousness. We've demonstrated that it's possible1 to turn it off, actually, by giving people a particular suggestion,1 and as a result of that, their experience changes markedly.1 I want you to think for a second, just for the sake of a paradigm.1 Think of a person who is lifting his hand, let's say...performing1 a particular movement, and then think of the same person performing1 the exact same motion under a different instruction. For example,1 let's say that this person is under some hypnotic spell1 or hypnotic induction, and we tell them, "You're not actually lifting"1 "your arm; it's a helium balloon that is connected to your hand,"1 "that is lifting your arm." So he is basically performing the exact same1 motion, but now, it's the helium balloon as far as he's concerned1 that is performing the motion, not him.1 We have today studies that look at these things very carefully,1 so that from an observer's standpoint, when you're looking1 at the performance of this person,1 they're performing exactly the same thing. You cannot see,1 from the outside, a difference in the output of the behavior.2 But in terms of what's happening in the brain, it's2 a world of a difference, because in the first case, they were2 raising their arm out of their own volition,2 and this was happening to them because they wanted this to happen,2 and in the second case, this was happening to them. Of course, you know2 and I know that this is not the case, because...there was2 no helium balloon. I was there; I checked. There was no helium balloon.2 But they were under the impression that there was a helium balloon2 and as a result they performed exactly the same motion.2 You can put sensors on the arm and you can use accelerometers and2 all these things in order to see that the motion is exactly the same.2 But you can also image what's happening inside the brain, and what's2 happening inside the brain is a world of a difference between these2 two conditions. So it's quite clear that in terms of agency,2 whether you are the author, whether you are doing something2 or something is happening to you, whether you are the choreographer or2 something is being choreographed for you, these things actually2 change our experience in a big way, although2 maybe from the outside the behavior looks the same. So that's2 another reason that there's a trend, there's a shift toward focusing2 on what's happening inside the brain objectively.2 We do have the technology to do this, and2 what we're missing right now is paradigms that are judiciously ethical,2 that the scientific community can decide and embrace and say,2 "this is good. I like this. This is ethical; it's going to fly"2 "by the ethics committee, it's going to be embraced not just by"2 "the ethics committee; by the public."2 "People are going to say, "this is good. This is ethical. I can see how"2 "I can learn from this," and it's going to be scientifically sound2 in the sense that a lot of scientists are going to agree2 we have a lot to learn from this. This is really important stuff2 that we're going to learn from. Now, just because I don't2 have much time, I'm going to skip these slides. So the first thing that2 you have to understand, and that people have to understand, is that2 we have a lot of holes in our scientific toilet paper. It's really2 important to understand this, especially when it comes to consciousness.2 Consciousness is a young field, and a lot of people have been2 dealing with consciousness from... schools of theology...from2 perspectives of martial arts, from the perspective of2 hunters and gatherers, from the perspective of survival, and so on.2 Science comes in and we have this2 trajectory that is very psychological science, cognitive science,2 neuroscience-stamped. Right now, brain science is in vogue.2 Believe it or not, it is. That's why people are sort of interested,2 they're beginning to get interested in these lacunae because2 people are also beginning to understand from other fields that,2 for example, the universe is 96% dark matter and dark energy,2 and we can't even observe it. There's a certain sense of humility2 and humbleness that comes with that, because suddenly...you2 study physics and they tell you "there's an electron...it rotates"2 "in a particular way," and then suddenly you learn that 96% of2 the universe is actually...does not conform with that model. We don't know.2 When we say dark matter, and when we say dark energy,2 as a scientist, I mean it in the epistemological sense. I don't know.2 It's dark because I don't know. It's in the dark. So you see,2 particularly as scientists, it's very important to understand the limits2 of your own knowledge, of your own technology and so on, and also2 to see the potential of what you can do.2 I think that very few scientists would dispute or would argue2 that today, consciousness studies, and studying2 altered consciousness, is an important field.2 Very few people would argue against that.2 I think that the question would be how to study it, and what is2 considered to be a judicious approach and a good sound2 scientific paradigm. And I think that is beginning to2 happen because on the one hand, we have this entire array of brain toys2 that is at our disposal in a big way, and prices are dropping.2 They're getting more and more affordable. Before...you needed to be2 extremely wealthy in order to do these studies. Today, you really don't.2 You can do studies not on a shoestring budget, but on much smaller2 budgets, and, with the right kind of question, you can actually ask2 some very meaningful things that could have clinical relevance,2 or could actually have theoretical relevance for scientists.2 I'll give you an example, and you'll give me the one-minute or2 two-minutes heads-up. So, think about it this way.2 Let's say you have strep throat.2 This is a favorite example of mine. I assume many people here2 had strep throat at some point in their lives. Very common thing.2 Modern medicine has the right answer for you. If you're not2 allergic to penicillin, they do a quick swab and they send it to the lab,2 they identify the bacteria. They give you penicillin.2 You don't need to come back. Ten days later, you're going to be fine.2 If you take your penicillin, you're going to be fine.2 But this kind of medicine almost doesn't exist out of strep throat.2 It's only with strep throat that we can do that. With other things2 in life, you have to go back, and there's a lot of trial and error2 with the drugs, and we're not sure what's happening,2 and it's not so deterministic. We are not so fortunate2 to have this kind of medicine.2 So what we're beginning to understand is that2 there's a lot of factors. A lot of factors actually play on2 medicine and on biology that are non-drug. Sometimes2 the interaction of drug and non-drug factors is a lot more potent2 than just drug factors or just non-drug factors.2 That interaction of drug and non-drug is something that has2 come to the forefront of the scientific...thinking only recently.2 Until recently, you couldn't even talk to scientists,2 or let's say clinical, clinicians, practitioners, and talk about2 non-drug factors. Everything was about biologically driven things.2 Today, people are beginning to talk about transcultural psychiatry.2 People are beginning to understand the importance of the influence2 of culture, the influence of upbringing and things of that nature2 in the effect of specific drugs. We're beginning to understand,2 for example, how people who are highly hypnotizable respond to2 suggestions differently from people who are not2 highly hypnotizable and what is the genetic makeup of these people2 and so on. So in addition to the neuroimaging revolution,2 we also had the genomic revolution. We can actually identify2 people with specific genetic polymorphisms who are likely2 to be more susceptible to particular manipulations that are either2 psychological or drug, by looking at genetic polymorphism.2 It's receptors that are going to respond more or less2 based on your genetic makeup.2 If you take this information, you put it together, you can2 actually get a preliminary blueprint to a conscious experience.2 The conscious experience that a lot of people focus on is the2 conscious experience of pain, because it's very clinically relevant.2 But there's a lot of relevance to altered consciousness,2 and consciousness studies that go beyond pain.2 In summary, what I want to say, basically, and I wrote this down2 so I don't get it wrong...I wrote something like thi ur understanding2 of altered consciousness, let alone common consciousness,2 is full of holes, as you can see here. One way to bridge and fill2 some of these lacunae should come from experiments.2 These experiments should, in my opinion, would include2 psychedelic substances. The trick, however, is to design2 an experimental approach that is scientifically sound on the one hand2 and judiciously ethical on the other hand.2 I believe that such a marriage is possible. Moreover, scientific2 understanding of altered states will likely shed light on practices2 largely unique to our species. I'm talking about2 things like spirituality, phenomenology, and their derivatives.2 The last thing that I want to say about neuroimaging2 and about consciousness studies before we open the floor for questions2 is that I detect, sometimes, some kind of a silo phenomenon2 between hardcore scientists and people who are non-scientists2 who are trying to convince scientists that something is interesting.2 Remember, and this is something that I can tell you from2 personal experience, remember that scientists, as dogmatic and2 as anal as they might be, are people. They're people.2 There's something in science that is called the vividness effect.2 You can talk about something all you want, but once you experience it,2 you change your position on something because2 you've experienced it. It becomes personal...now it's personal.2 Before, it was just a theoretical idea... so there's something to2 be said about the vividness effect, and the fact that most people2 who have opinions, usually a particular kind of opinion about2 certain things, have never experienced, or know very little about2 these things. If you do a survey, for example, among scientists, and2 particularly scientists who are in these kind of fields,2 you will discover that in addition to a skeptical conservative kind of2 stance that they have from being a professional scientist,2 where you need to have that in order to practice that profession,2 sometimes you can be skeptical and be conservative and do cutting-edge,2 adventurous, innovative research that is trail-blazing and2 would appeal to a large audience because you have experienced2 something that basically gives you the fuel or gives you2 the impetus to actually go and do that. Before, you just...had no idea2 of what that was like. So that's a very important realization2 that I think a lot of people are missing on when there's3 conversation in these realms. I'd like to close it here, because Kelly3 is signalling to me nervously that we're running out of time,3 and I'm going to be here for a few minutes, or as long as it takes,3 if you need more time to ask me questions3 after the formal question-and-answer period. Thank you very much.3 [applause]3 [moderato We have time for just a couple questions.3 uan Acosta. You answered my question these last two minutes.3 That is, I wanted your view on...3 I do consciousness studies using EEG. I'm a neuroscientist. If the3 scientists should have these experiences that they are studying,3 in the lab or in other settings... I think it's important that they3 have these experiences, at least that they know the terrain3 that they're getting into. What's your view?31:0